- Home

- Sybil Marshall

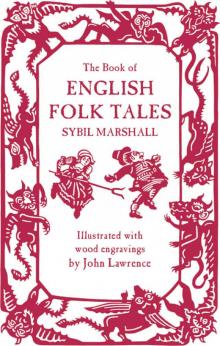

The Book of English Folk Tales Page 5

The Book of English Folk Tales Read online

Page 5

Others have put forward theories that latter-day fairies represent the remnants of pagan animism, when every tree, river, lake and so on had its own spirit residing within it; and that the small, swarthy, hairy beings now termed dwarfs or brownies are all that remain in folk memory of a pre-Celtic ethnic group with different but well-defined physical and behavioural characteristics.

Most recent is the explanation that all the ‘Little people’ can be accounted for psychologically, and belong almost exclusively to the field of psychological erotica.

The Devil

The Devil is hard to pin down to one category, so many and various are his antics. He seems everywhere to have been so busy changing the landscape by throwing up earthworks, or dropping apronfuls of enormous stones, that he must figure in the etiological section. On the other hand, his involvement with saints of the early Christian Church, and his interference in the siting of ecclesiastical buildings can surely be traced back to history, whatever wild growth of fantasy has accrued round the historical roots of the tales. One can but suppose that the numerous skirmishes between the Devil and the saints (in which the latter are almost always victorious, and the evil one discomfited) are probably all that now remains of the long struggle for supremacy between the early Church and the strong and attractive paganism of the folk. This comes over quite strongly in ‘Old Nick Is a Gentleman’, a Yorkshire tale in which the Devil is much more akin to the medieval lay conception of him than that of later Christianity. This Devil is related to the one who, in one of the medieval miracle plays, persuaded Mrs Noah to dance with him as the Ark set sail, and to the chap who ‘has all the best tunes’.

Witches and wizards, the servants or adherents of the Devil, belonged in the first instance to supernatural beliefs, but as time went on, became more and more part of history. The hag who appeared to the king in the etiological tale of the Rollright Stones belongs perhaps to fantasy; the witch and wizard of Tring are surely part of history, for it was all-too-ordinary flesh and blood that suffered and died there at the hands of its all-too-ordinary human superstitious peers.

While supernatural beasts (black dogs and white rabbits, etc.) are not included in this sub-category, some widespread apparitions such as the Wild Hunt, whose appearance bodes death and destruction, are linked with the Devil and must be remembered here.

Omens, Warnings and Fetches

The mysteries of life and death form the matter of the largest but least definable group of tales of the supernatural containing, as it must, the endless variety of hauntings and omens all presaging death or calamity. Many are the omens of death belonging to the field of ordinary superstition (for example, the falling of a mirror or a portrait from its place on the wall without apparent cause), and have no place in this collection. Others, such as the appearance of the ghostly ‘fetch’ to a doomed person, are widespread as tales. The Death Coach, the Wild Hunt (called in Yorkshire ‘the Gabriel Ratchets’) and some spectral beasts which foretell death may, however, stray into other categories.

Ghosts

Ghosts come in infinite variety, including those heard, smelt and felt, though never seen, while those that appear often do so, apparently, to no purpose. Some families have ghosts that are as familiar to them as the living; ‘always ’ere, ’e is, cluttering up the place’, as one old woman said indignantly when she found the ghost of a lad who had been killed on a motor-cycle sitting yet again in her favourite chair; or, as my paternal aunt recounted to my father one morning, with regard to a spectral visitation from her late husband, ‘I said to him, “Look ’ere, John, if you don’t keep to your own side o’ the bed, I shall ’it you with my stick, that I shall!”’ Some appear with benevolent purpose to their loved ones, as when my maternal grandmother came to the bedside of my aunt, who had suffered long with crippling lumbago. ‘Poor Lizzie! Where does it hurt?’ said my ghostly Grammam, and proceeded to rub the afflicted spot with a soothing if uncorporeal hand, before drifting away again into nothingness. In the morning, the pain had gone, and never returned though the aunt in question lived to be eighty-nine.

I could go on; how does one account for the fact that very recently a niece of mine lying at death’s door in a hospital in Central Africa looked up to find my father, her beloved ‘Grandad’, who died when she was eight, sitting on the foot of her bed ‘in his shirtsleeves, just as if he had come in from the farm’, and encouraging her to hold on to life? Of course, all kinds of rational explanations can be found – but the stories remain, and get folded into the body of folklore among the rest like single handkerchiefs in a crammed linen closet. The famous ghosts, like Lady Hobby of Bisham Abbey, Berks, are persistent through the ages – in this case the purpose being to show some signs of remorse, apparently, while others seem only to want to avenge wrongs done to them in life.

A great many of the folk-ghosts are those of people who died violent or untimely deaths by accident, war, murder or suicide. I was discussing this recently with an elderly cousin who reminded me that my paternal grandmother and my aunts held a firm theory with regard to it. They believed (as I think some modern geneticists have recently put forward) that every child born brings with it a pre-determined span of life. If, for any reason, this life was cut off before the completion of the allotted span (said my grandmother), the spirit was compelled to finish out its time without the aid of its body. A most attractive theory, surely – until one remembers the millions of young lives brought abruptly to an end in the First World War – the influenza epidemic of 1918 – the civilian as well as military casualties of the Second World War – the victims of earthquakes and tidal waves and floods and hurricanes in the last normal lifespan of six or seven decades! It’s a wonder those of us who still do keep body and soul together can even fight our way through the swarms of unhappy spirits still ‘doing time’. But ghost tales go on.

Unfortunately, many a ‘ghost story’ is not a story at all, but the mere reporting of a sighting. A story needs a sequence of beginning, middle and end, and in the case of a good ghost story it really demands a cause, an apparition, and a consequence as well. Because of this defect in the tale, many a well-attested ghost does not make its appearance between the covers of this book.

Unquiet Spirits and Spectral Beasts

All ghosts are, one supposes, ‘unquiet spirits’, but there seems a distinction to be made between the orthodox sort of ghost appearing with some regularity and uniformity of place and time, and the spirit doomed to wander, like the Flying Dutchman (not included in this volume) or John Tregeagle. Then there are tales of suspended animation, when the spirit leaves the body to return at will, and tales of bodies which, though bereft forever of their spirits, defy corruption (as in the case of Saint Edmund). There are bodies (particularly severed heads) which refuse to remain buried, like that of Dick o’ Tunstead.

Encounters with ghostly creatures, as distinct from those in human form, are by no means uncommon. Such hauntings range from unspecified beasts heard panting and padding behind, or seen only as vague and undefined shapes and presences producing hair-raising sensations of cold and terror, to the ghostly white rabbit of Egloshayle. They also include widely held beliefs in the Wild Hunt and the many regional variations of Old Shuck, the shaggy black dog of East Anglia.

Giants

Huge beings, oversized humanoids, have a natural tendency to evil and destruction, and perhaps come nearest to fitting the psychological explanation of belief in the supernatural. They are akin to the mythical giants of Teutonic paganism, of which they may be relics.

Place Memory

There has been an upsurge of interest in recent years in ‘the old straight tracks’, that is the prehistoric pathways that ran from one high point in the shortest possible distance to the next. The spots at which these ancient ley-lines crossed each other are probably not only the oldest, but the most frequented of meeting places, either for good or ill. There is a growing belief that ‘something’ is left, a force that still resides in such places

, and that can still be felt by and even influence the living. One interesting theory is that ‘accident black-spots’, at which unaccountable accidents continually occur, may coincide with crossing points of the ancient ley-lines. Many motorists who have been involved in such accidents have said, in puzzled attempts to reconstruct the happening, ‘it was just as if something or somebody simply took hold of the steering wheel and pulled’. Very few such tales have so far been collected in detail, though others of haunted buildings (churches in particular) that stand on such spots are beginning to be significant in number.

The story left by my brother, ‘Time to Think’, could possibly be included in this category. The theory of constant happenings impressing themselves on places is really the basis of a great many ghost stories; it is the shift of emphasis from the ghostly protagonist to the precise locality that is a little different. I quote from Haunted East Anglia (Fontana) by Joan Foreman:

I have not been able to discover the history of The punting woman’. No doubt in life her journeys to and fro by punt were regular enough to constitute a habit. This repetition of what was in life a regular practice is a feature of many ghost stories. It is as though a pattern or rhythm had been developed and superimposed upon the material surroundings, so that when the instigator of the pattern was no longer able to carry it out, some imprint of the sequence still remained in the physical surroundings.

Colin Wilson, in Mysteries (1978), has much to say on this question, and on ‘the ghouls’ of the next category.

(B) The Relics of History

A second category, probably larger than the first though possibly not so popular, is composed of tales concocted around a thread of historical truth. In these, folk-embroidery adds a great deal to folk-memory, and weaves new tales that often bear little resemblance to the original, perhaps because of a psychological need to create heroes or saints to serve as examples, or to provide scapegoats for ritual verbal sacrifice, in order to expiate some deeply hidden folk guilt. Such creative embroidery of detail has, for instance, changed a low-lived, murderous thug like the real Richard Turpin to the romantic Dick astride gallant Black Bess, and sent him flying through the night from London to York (or to one of a dozen or more other places which claim to have been his destination); or, in the same fashion, has loaded some nameless, excommunicated medieval cut-throat outlaw with the trappings of noble birth and chivalry, and set him up as a defender of the poor against the rich oppressor, and thereby created the enduring legend of Robin Hood.

Saints and Martyrs

Saints, like the Devil, are hard to pin down, so miraculous and extraordinary are their doings; but whatever the monkish chroniclers, who were their first biographers, have written down about them, two facts have to be taken into account. One is that there was almost certainly some historical character at the bottom of the legend; the other is that the monks stated what they had heard, no doubt orally, from the folk, who in some cases had already had several centuries to add to the original story as in ‘St Eustace’s Well’, and Gervase of Tilbury’s tale about the knight of Wandlebury. The same applies to ‘sad stories of the death of kings’ (as of Edmund), and the more spectacular activities of monks and nuns (‘Ednoth’s Relics and Thurkill’s Beard’).

Witchcraft

There is a fairly clear demarcation line between the witches of fairy story and the belief in witchcraft that has played so barbarous a part in recorded history. The witch of the fairy story (as, for example, in ‘Hansel and Gretel’) seems to be in some ways a female counterpart of the giant, in so far as she is an embodiment of the concept of universal evil and cruelty, as the giant is an embodiment of uncontrollable power and ruthless might.

The historical witch, on the other hand, is flesh and blood supposedly endowed with supernatural powers as a result of her dealings with the Devil. Fear and religious fervour combined were enough to enable a chance word, an angry look or simple coincidence to turn a neighbour into a witch overnight, as a story such as ‘Lynching a Witch’ demonstrates.

Ways of Getting a Living

There is no lack of strange ways of earning one’s livelihood today, and the frequency with which they appear as news items in or on the media proves the attraction they still hold for the more conservative among us. We are just as intrigued with some occupations and professions in the past, though there is no reason to suppose that those who engaged in them thought of their ways of earning a living as anything but as ordinary or as necessary to their survival and way of life as, for instance, piloting a jet aeroplane or diving from a North Sea oilrig is today. Witness the eighty-eight-year-old Deal smuggler who told Walter Jerrold, ‘Good times, them, when a man might smuggle honest. Ah! them were grand times; when a man didn’t go a-stealing with his gloves on, an’ weren’t afraid to die for his principles’ (Highways and Byways in Kent).

But just as there are now pilots with hair-raising tales of hijacking, or divers with accounts of cheating death on the sea-bed by a hairsbreadth, so there were once crusaders to whom out-of-the-ordinary adventures happened, smugglers whose artful trickery tickled the popular fancy, wreckers whose deeds were more than usually brutal, or body-snatchers who stopped at nothing in their macabre nocturnal doings. So such stories as ‘Bury Me in England’, ‘The Vicar of Germsoe’, etc. have been remembered where thousands of others of the same kind have been let slip from memory.

The Religious

The latent antagonism between Church and State that ended with the dissolution of the monasteries, and the proliferation of religious houses throughout the Middle Ages no doubt led to a great deal of homely gossip among the folk with regard to the reported ‘goings on’ of the religious, which in turn and in time solidified into tales that are of a different nature from those recounting the holy lives of saints.

Causes Célèbres

Another group is formed by tales of people whose deeds found popular fame or notoriety in their own time, but who have been largely forgotten since, except in their own locality. Charles Radcliffe, Earl of Derwentwater, is undeniably part of history, but the details of his exploits as the Gilstone Ghost belong only to folklore. In the same way, the sordid fact of Gervase Matchan’s crime was real enough, but it is folk-detail that has kept his story alive in Huntingdonshire.

(C) Localities, Origins and Causes

Most stories are located somewhere or other, of necessity, though as we have seen, the same tale may be claimed by more than one geographically distanced region. However, there are some which cannot, because of their intrinsic ingredients, be moved.

Etiological Tales

Such tales give folk-explanations as to the origins of earthworks, curious rock formations (‘The Parson and the Clerk’), standing stones (‘The Rollright Stones’), causeways, and so on.

Notable Characters

These were men and women who were physically or metaphorically larger than life. Such physical giants as Jack o’ Legs have to be distinguished from supernatural giants like Bolster and Jecholiah, of St Agnes’ Mount. In the same way, the colourful character of Old Mother Shipton of Yorkshire does seem to have existed in the flesh, whatever the clouds of sorcery and magic that have since enveloped her.

Nine Days’ Wonders

All who know village life as it used to be (where anyone’s business could be everybody’s business in the space of twenty-four hours) will recognize the validity of including as folk tales the kind of local happenings that qualify as ‘nine days’ wonders’. Great storms or plagues of midges, a ‘rain’ of baby frogs or the appearance of the aurora borealis, a multiple birth or the discovery of the vicar with the village hoyden behind the church organ, the latest bit of effrontery by the local rapscallion or a particularly harrowing deathbed – any or all of these would be discussed and enjoyed until they ballooned into something to be remembered and recounted to the younger generations. When anything of the nature of the Campden Wonder or the Girt Dog occurred, its translation into a folk tale was only a matter of time.

(D) Fabulous Beasts

Dragons (i.e. any outlandish creature) play an important role in folk tale, as huge and fierce corporeal beasts from which the localities they frequented had to be saved by some courageous local hero – as in Durham, where the Wyvern of Sockburn was slaughtered after a ferocious struggle with ‘the Conyers Falchion’, a replica of which, already in its own right seven hundred years old, is still to be seen in the Cathedral Library; or as in Pelham, Herts, where the Devil’s dragon was overcome by one Piers Shonkes, and with the Laidley Worm of Yorkshire.

(E) Domestic and Simpleton Tales

This is a category made up largely of domestic or local community tales. To it belong husband/wife contentions, such as ‘Get up and bar the door’ and ‘The Last Word’. (The latter I took in with my suppertime bread and milk at about the age of four, when I asked why one or other of my parents so often said ‘O, Scissors!’ to the other.) In them, too, the wise fool (see the stories of the men of Gotham), or the village simpleton (‘Numbskull’s Errand’) figure large; most areas have a legendary character to whom foolish sayings are attributed. In my own case, it was somebody called Fred Tatt, who constantly gave out such pearls of wisdom as ‘the longest ladder I ever went up were down a well’.

These stories simply do not lend themselves happily to print. For one thing, they are essentially oral. The humour in them is so delicate and subtle that trying to pin it down in written words destroys it, like attempting to catch a soap-bubble. They need telling in the vernacular, too, for the full flavour to come through – and they depend a great deal for effect on the eye-to-eye contact between the teller and his audience. There is the change of facial expression, for example, the lifting of a quizzical eyebrow, the deliberate lowering of the voice to a mournful monotone so as to be able to raise it again for a dramatic punch-line – all this and much more is lost in print.

The Book of English Folk Tales

The Book of English Folk Tales