- Home

- Sybil Marshall

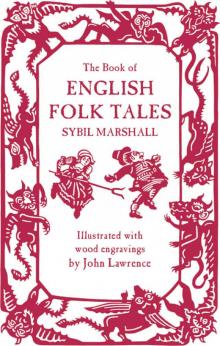

The Book of English Folk Tales

The Book of English Folk Tales Read online

SYBIL MARSHALL (1913 - 2005) was a writer and educator. Her texts on educational theory pioneered progressive teaching methods and influenced several generations of educators. She also served as an Education Adviser to Granada Television, where she oversaw the celebrated program Picture Box, which reached more than 300 million schoolchildren over 23 years. In addition to her books on education, she wrote her fictionalized autobiography as a trilogy of novels, published by Penguin. She won the Angel Prize for Literature for Everyman’s Book of English Folk Tales.

JOHN LAWRENCE is the eminent English illustrator and wood engraver. He has twice won the Francis Williams Award for illustration (sponsored by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London) and twice been runner-up for the Kurt Emil-Maschler Award. He lives in Cambridge.

Copyright

This edition published in the UK and the US in 2016

by Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E: [email protected]

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales, please contact

[email protected]

or write to us at the address above

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact

[email protected], or write to us

at the address above

First published 1981

Text © Sybil Marshall, 1981

Illustrations © John Lawrence, 1981

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The right of Sybil Marshall and John Lawrence to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1524-0

For Ewart with Love

Contents

About the Author

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

The Supernatural

The Little People

Seeing Is Believing

‘Aye, We’re Flitting’

The Farmer and the Bogle

Jeanie, the Bogle of Mulgrave Wood

Visions of Fairies

The Weardale Fairies

The White Cap

The Devil

St Dunstan and the Devil

The Black Monk’s Curse

The Devil’s Armful

Old Nick Is a Gentleman

Omens, Warnings and Fetches

The Wild Huntsman

The Phantom Coach

The Mysterious Cannon Ball

The Fairy Fetch

Ghosts

The Ghost of Lady Hobby

Herne the Hunter

‘Gold, Ezekiel! Gold!’

Unquiet Spirits and Spectral Beasts

John Tregeagle

Dick o’ Tunstead

The White Rabbit

Giants

A Yorkshire Giant

Bolster and Jecholiah

Place Memory

Time to Think

The Phantom Army of Flowers Barrow

Knight to Knight

The Legend of Lyulph’s Tower

The Relics of History

Saints and Martyrs

England’s First Martyr

Edmund the Holy

St Eustace’s Well

Ednoth’s Relics, and Thurkill’s Beard

Witchcraft

The Witches of Tring

Lynching a Witch

Possessed by the Devil

Ways of Getting a Living

The Vicar of Germsoe

The Wrecker of Sennen Cove

Bury Me in England

‘A beautiful lady whose name it was Ruth’

The Smuggler’s Bride

Jack o’ Both Sides or The Biter Bit

The Hand of Glory

The Religious

O Horrid Dede!

Good Sir Thomas and Friar John

Causes Célèbres, High and Low

The Gilstone Ghost

Truth, and Murder, Will Out

Localities, Origins and Causes

Etiological Tales

The Rollright Stones

The Hurlers

The Parson and the Clerk

The Wedding at Stanton Drew

Notable Characters

Jack o’ Legs

William Wake of Wareham

Old Mother Shipton

God on Our Side

Sir Andrew Barton

Nine Days’ Wonders

T’Girt Dog of Ennerdale

The Campden Wonder

The Boar of Eskdale

Fabulous Beasts

The Devil’s Own

The Laidley Worm of Spindlestone Heugh

Mathey Trewella

Domestic and Simpleton Tales

The Last Word

‘Get up and bar the door’

Wise Men Three

The Twelfth Man

Numbskull’s Errand

Moral Tales

Belling the Cat

Simmer Water

Wild Darrell

The Marriage of Sir Gawaine

Introduction

It is a curious characteristic of intelligent people that they only begin to value their cultural inheritance highly when it is in danger of disappearing for ever over the cliff-edge of time – at which point they seize the tip end of its tail and exert tremendous energy in trying to haul it back. Usually what happens is that the tail comes away in their hands, and the body is lost – to become, in time, ‘the evidence’ by which the archaeologist supports the anthropologist in reconstructing a picture of a period or a society gone by. So it was with the great corpus of folk tale that must have existed orally everywhere in England until the great changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Masses of people pulled up their roots in rural areas and moved to the growing towns, living for the first time among people from other districts who were, to all intents and purposes, ‘foreigners’ to them. There can be little doubt that they all took their culture (and their tales) with them, and that for a short period, at least, there would be interchange and melding, resulting in modification of details carefully preserved until then. But such a period could not have lasted long, because the towns themselves began to generate a culture of their own which, once it had become established, chose to despise its own rural origins. (Two-generation industrial workers in Peterborough made no bones about referring to us fen-dwellers from Ramsey as ‘country bumpkins’, even though we knew them and their families personally, and could still point to the tiny turf-diggers’ dwellings from which their grandfathers had walked to try their luck in the town.)

I found an astonishingly clear example of the survival of this attitude in a book I read just recently. This was a sociologically-slanted survey of a street in Northampton, where a community spirit has survived because so many of its present population have a common rural background. The author appeared to deplore this shared thread of identity, in particular as it is evidenced by the continued use of country idiom still retained from former times.

The passage roused in me emotions of anger and distress amounting almost to fury. For one thing, the very idioms he chose to castigate were those that might very well rise to my own tongue at any moment anywhere, while chatting in a village shop or delivering a lecture at a university; but

in another, less personal but much stronger fashion, I was perturbed by the implied pejorative attack on this sort of language in general.

I regard such idiom, and its metaphorical content, as what Gerard Manley Hopkins called ‘the native thew and sinew of the language’. To the modern town-bred author, it appeared to be a ready-made, almost ‘processed’ or ‘convenience’ language denoting in its users sluggish, unoriginal minds that had not progressed at all since leaving the lumpish countryside. In my view, such idiom indicates the essential nature of our linguistic heritage. It is a point to which I shall return.

The terrible conditions of the early industrial towns were adverse to the preservation of oral rural culture because there could have been little time or energy left for tale-telling at the end of a working day; and in any case the spread of literacy, beginning in the towns and extending gradually to the surrounding countryside, removed the need to memorize, so that the actual faculty for recalling and recounting an oral tale began to atrophy. The result was that the great body of oral tradition was already a long way down the cliff-face when the antiquarians of the nineteenth century grabbed at what was left and managed to save a considerable amount. From Sir Thomas Browne’s Pseudoxia Epidemica (1646), through Aubrey, Brand, Strutt, Sinclair and Hone (plus the Gentleman’s Magazine) there was a thin but tough thread of continuity to help them in their task, and the sudden surge of interest culminated in the foundation of the Folklore Society in 1878. These nineteenth-century collectors were, almost without exception, educated men who were collecting as amateurs, in the strictly literal sense of that term; but it was from ‘the folk’, and mainly the folk of rural England, that they gathered the tales – and from our vantage point of the end of the twentieth century, it is easy to understand some of their difficulties.

In the first place, the countryman has no predilection for being either despised or exploited, and his shrewd intelligence warned him that educated clergymen out with their notebooks were ‘after something’, which probably had the effect of sealing an otherwise loquacious labourer’s lips. If the listener showed the least sign of condescension, he would in all probability either receive in return nothing but a series of unintelligible grunts, or be sent away in possession of what we should now designate as ‘a load of old cobblers’. We have a strangely parallel phenomenon occurring today, when sociologists with tape recorders are setting out from universities to make surveys of villages here, there and everywhere. This is a laudable enterprise, in danger of foundering badly if the researchers do not understand absolutely the nature of the people they are interviewing, and fail to set out in possession of enough sociological knowledge to inform them how to begin on their task.

When, on retirement from full-time employment, I chose to go back to my native countryside, I was somewhat surprised and mystified to find myself viewed very much askance, and certainly not accorded the welcome I would have expected to be given to a fen-tiger returning home from choice and a genuine love both of the area and its people. My book Fenland Chronicle had proved that, and indeed had been very popular in the area. So why the obvious suspicion of me?

Then one day someone asked me outright if I was the person responsible for a recently published sociological survey of a nearby village. Resentment at conclusions drawn (and stated) from what had been given freely in conversation by the village people had, apparently, spread across the fens far and wide.

I heard another example only a week or two ago, of a team with a tape-recorder researching a village in a different area. They started by visiting the oldest couple, explained their purpose, and switched on the tape. Then the interviewer said to the old man, ‘Tell me first of all everything you can about your mother and your father.’ The old man remained dumb, and not another word from either of the couple was forthcoming. The reason, of course, was that the old man had been born illegitimate in a time when bastardy was an ineradicable stain on the character – a fact that a modern youngster was not in any way likely to appreciate. Any other beginning would have got him further!

We have the testimony of Arthur N. Norway to the truth of my assertions. When travelling in the West Country gathering material for his volume (published in 1919) in the Highways and Byways series, he met and commented upon it:

Tales such as these flutter round Devon as plentifully as bats flit across the chimneys of an ancient manor house; for in both Western counties the Keltic temperament has produced its full crop of superstition. There is hardly a cottage in the West where the incidents of domestic life are not affected almost daily by the welling up in the hearts of the people of some belief or prejudice so ancient that no centuries which we can count exhaust its life, but which has risen generation after generation, throbbing today as powerfully as a thousand years ago, if more secretly. Those who search openly for these beliefs will seldom find them; for the people hide them with a sedulous anxiety which springs, partly from pride in the old faiths which have become entirely their own since the world rejected them, and partly from timidity lest what they cherish and believe should be laughed at by superior persons. And so not the most sympathetic inquirer will learn much by directly questioning the peasants. He will be met at every turn by ‘Augh, tidd’n worth listening to by a gentleman’, and no persuasions will break down this attitude of reserve.

In another place, the same author touches upon one of the factors controlling the countryman’s attitude. It is the credulity of the listener. If he is prepared to believe, or, at any rate, in Coleridge’s words ‘to suspend disbelief’, then he is likely to be rewarded. It is obvious that it was this factor of credulity that hindered and perturbed a good many of the nineteenth-century collectors themselves, for in the hey-day of Victorian doctrinal Christianity, any semblance of belief, even half-admitted, must have seemed like heresy. A case in point is the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, a clergyman to whose interest in folk tales and folklore in general we owe a considerable debt. His Book of Folk-Lore begins with a description of how he himself (as a child) and subsequently his young son, had actually seen ‘the little people’; but this is followed immediately by an attempt to explain away the visions, by blaming them on imagination, derived from the too-vivid tales they had heard from their country nursemaids. It is, one feels, a sort of whistling in the dark by the reverend gentleman, to keep at bay any temptation to believe on his own part; but a few pages farther on, he tells the story of how the local sexton opened the grave, and the coffin, of his (the author’s) grandmother, a formidable old lady known as Madame Introduction Gould. When the sexton raised the coffin lid, the old lady sat up and glared at him. The sexton beat a hasty retreat, but Madame Gould followed him all the way home, so that when in terror he flung himself into bed by the side of his wife, she roused, and also saw the dead woman standing over them. This story is related by the Reverend Gould without a hint of any kind that he doubted the sexton’s word. Madame Gould had been seen by too many others in different places for his doubts on this to be genuine ones. The whole of the rest of the book displays the same ambivalent attitude. Again, there is a parallel today, in the recent rediscovery of ‘magic’ and ‘the paranormal’, in the growing interest in dowsing and ley-lines, and extrasensory perception of all kinds (as investigated, for instance, in the writings of Colin Wilson). The things that are not comprehensible in ordinary terms are ‘explained away’ by a variety of theories, mostly psychological – but they are not denied.

The folk who preserved, generation after generation, the stories we now call folk tales would, I feel sure, never have denied them. To understand the nature of the folk tale (whatever the definition of a folk tale may be), it is absolutely necessary to understand first the nature of the folk and their language, which in its turn reflects their thinking and their way of coping with life. They would not have asked, as Pontius Pilate did, ‘What is truth?’; but they would, if the truth of anything was being questioned, probably remark, ‘Truth’s at the bottom of the well’. In fact, they question not t

he existence or the nature of truth, but accept that it lies somewhere deep down and probably has to be searched for. And they use a terse and homely metaphor to express their philosophy, and expect other people to understand the extended meaning.

Writing in the introduction to his Teutonic Myth and Legend at the end of the nineteenth century, Donald A. Mackenzie states: ‘Not infrequently scholars, by a process of detached reasoning, miss the mark when dealing with folklore because their early years were not passed in its strange atmosphere.’ In this, perhaps, I have an advantage. I belong, unequivocally, to the folk themselves; people who are still born and bred in the tradition of tale-telling, listening, assimilating, eclectically remembering, and in their turn, recounting. In the ordinary way, they have no academic axe to grind, and seek no reward, not even that of private satisfaction such as motivates the desultory amateur collector. To hear and then disseminate such tales is as much a part of their ordinary fives as sitting down to Sunday’s dinner, or sluicing a sweating face with cold water. They appear to think nothing of, or about, the tales they tell, except for the pleasure of the telling, or, as the case may be, of listening in order to be able to cap one good tale with another.

To return for a moment to the present volume; there are many different reasons for publishing collections of so-called ‘folk tales’ beside the obvious one of giving the reader who likes such things some entertainment. They shed light, for instance, on history, particularly local history, by supplying details that the academic historian cannot find room for. The story of the Radcliffe family, as given in ‘The Gilstone Ghost’, is more likely to give an O-level history candidate a true grasp of the Stuart/House of Hanover conflict than many pages of dry historical ‘fact’ baldly stated. Equally, they can be regarded as matter relevant to the sociologist, providing sudden insights and examples of how common self-interest and group emotion operate, as in the local reaction expressed towards the fellow who made quite sure that ‘the witch’ of Tring did not escape drowning at her ‘trial’.

They cast, too, a gentle glow of illumination over the field of philosophy, demonstrating thought patterns and beliefs so old as to be almost instinctive, among people too uneducated to express them in accepted philosophical terms, but nonetheless very articulate when using their own linguistic patterns. And they intrigue the antiquary by sending him searching in his own mind after answers to questions with regard to the origins of some of these beliefs. The Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, for instance, derived the ubiquitous ‘death-coach’ stories in England from the Breton Ankou (La Mort, who travels about the countryside in a cart, picking up souls); but this in turn he connected with the Celtic goddess of Death, represented by the rude female figures carved in the chalk above some Celtic necropolises. In the same way, he thought our (once-popular) exclamation ‘What the Deuce?’ to be a reference back through the years to a belief in the god Tiu, the Anglo-Saxon equivalent to the Norse Tyr, the Latin Deus, Greek Zeus and Sanskrit Djous. Such amateur anthropological deductions pointed the way in turn to the other more scholarly works, for example, the brilliant seven-volume exegesis of Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough.

The Book of English Folk Tales

The Book of English Folk Tales